Southern Water's ghost from the past

The financial product that blew up the world in 2008 is haunting the highly-indebted privatised utility

If you thought Thames Water was complicated, just wait till you see Southern Water. It has a corporate structure of mind-boggling complexity.

But looking past the complexity, there’s something hauntingly familiar - a ghost from the past. The financial product that nearly blew up the world in 2008 is back, in a new form. And it is threatening to blow up one of the UK’s essential public utilities.

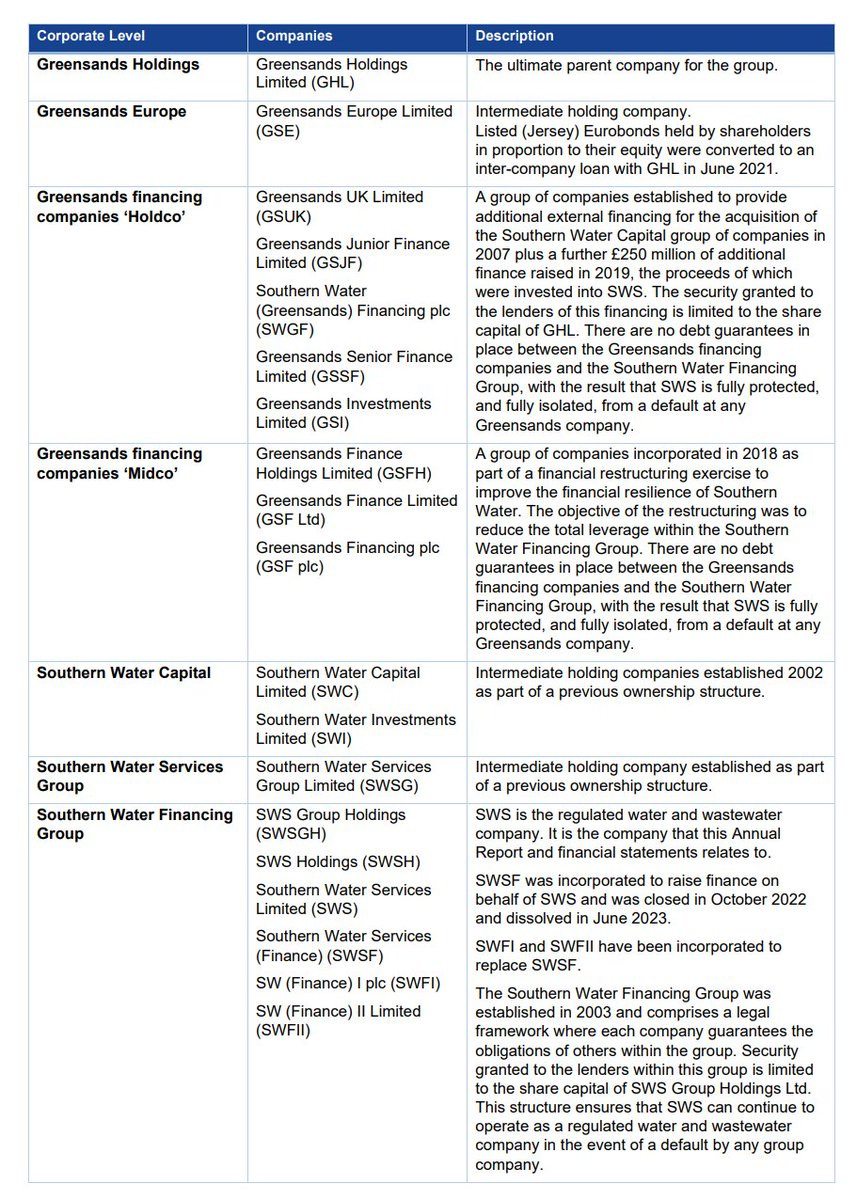

Making sense of Southern Water’s complex corporate structure

Southern Water, the regulated utility, is at the bottom of a corporate edifice resembing the Tower of Babel:

It’s not immediately apparent from this chart just how complex this structure is, so here’s a helpful table.

There are three nested corporate structures: Greensands Holdco, Greensands Midco, and Southern Water Financing Group.

Southern Water Financing Group is a Whole Business Securitisation (WBS) similar to that in Thames Water. It is ring-fenced from the rest of the conglomerate. The financing SPVs in this WBS, Southern Water Services Limited and Southern Water Services (Finance), were originally incorporated in the Cayman Islands. After the industry regulator, Ofwat, stomped on offshore financing in 2022, the Cayman SPVs were replaced with two onshore SPVs, SW (Finance) I plc and SW (Finance) II Ltd., and the bonds issued by the Cayman SPVs were novated to the onshore entities. As with Thames Water, the purpose of the holding company in the WBS is to make a permanent tax loss in order to reduce the utility’s tax bill.

Southern Water is the only operating company in the WBS and the sole source of cash. We could call the rest of this structure plumbing. It siphons cash from Southern Water and distributes it to various stakeholders.

And it has another purpose too.

Debt structuring

The two nested structures above the WBS, Greensands Holdco and Greensands Midco, both issue external debt. Each has a debt-issuing SPV: respectively, these are Southern Water (Greensands) Financing plc and Greensands Financing plc. The other companies in the structures exist to transfer the debt and the cash raised to other parts of the Southern Water edifice.

As with the WBS, there are cross-guarantees between the members of the nested structures. And there are also guarantees protecting the Southern Water WBS in the event that Holdco and/or Midco defaults on its debts. So the regulated utility will be able to continue trading even if the entire Greensands edifice collapses into insolvency. Thank goodness.

But why is the Southern Water/Greensands group raising external debt at three different levels in its corporate structure? Well, to explain this, let’s recall the “collateralized debt obligations” (CDOs) that collapsed so disastrously in 2008.

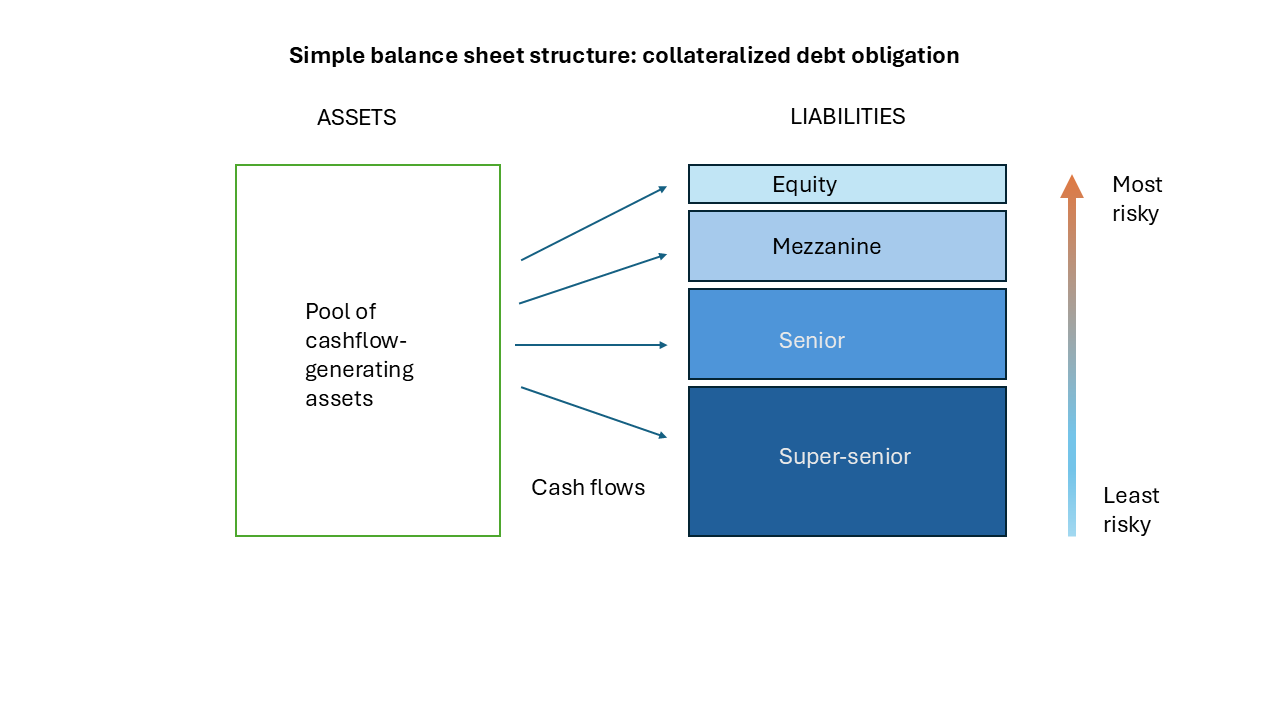

CDOs such as Goldman Sach’s ABACUS tranched a pool of assets by issuing securities of increasing riskiness, thus creating something that resembled a corporate structure:

Cash flows from the underlying assets service the debt in this highly leveraged structure. As long as those cash flows remain stable, everyone gets paid. But if they fail, then the claims on the underlying assets are distributed according to a strict hierarchy: super-senior debtholders first, then senior, then mezzanine, and only if there is any money left over do equity tranche holders receive anything. This is of course how distributions work in corporate insolvencies. The similarity is not accidental.

The interest rates paid on the different classes of security in this structure reflect their risk: interest rates on super-senior tranches are the lowest, equity tranche (also known as “toxic waste”) the highest.

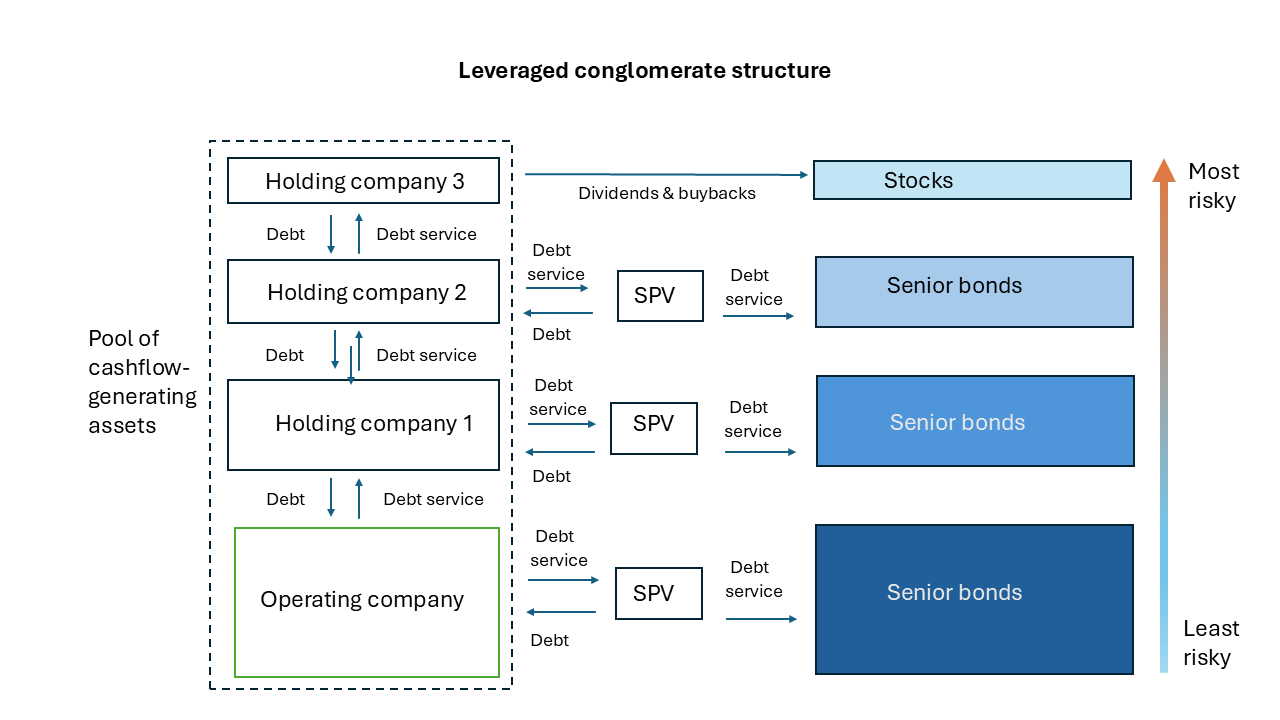

In the simple structure I’ve shown above, the assets and liabilities are all within the same legal entity. But they don’t have to be. In a complex corporate structure like that in Southern Water, cashflow-generating assets belong to the whole conglomerate. So debt can be issued against those assets at any level in the structure. It looks something like this:

All the bonds are classed as senior bonds. But the bonds issued by the holding companies are nevertheless subordinated, because of their position in the structure. The senior bonds issued by the operating company (opco) are “super-senior”, those issued by holding company 1 are “senior” and those issued by holding company 2 are “mezzanine”. The coupon rates and yields on the bonds reflect their position in the structure and hence their degree of structural subordination: the higher up the structure the debt is issued, the higher the interest rate.

Holding companies don’t themselves generate cash. But external bondholders want cash. So, to service their debts, the holding companies must extract cash from the opco. They do this by lending to companies below them in the structure, which in turn lend to companies below them. Eventually the cascade reaches the opco, and cash then flows back up the structure to the holding companies and their SPVs, enabling them to service their debts. The interest rate on these intercompany loans is set by management and can be higher than the interest rate paid to external creditors.

For regulatory reasons, transfers from the opco to its immediate holding company (within the WBS) can take the form of dividends rather than debt service, but the dividends are then sucked upwards in the form of debt service.

This is in essence Southern Water’s structure, though considerably simplified. Southern Water itself, the regulated utility, issues “super-senior” debt via the two SPVs in the WBS group. Greensands Midco issues “senior” debt via its SPV Greensands Financing plc. Greensands Holdco issues “mezzanine” debt via its SPV Southern Water (Greensands) Financing plc. There are explicit guarantees in place to prevent defaults at upper levels cascading to lower levels in the structure.

However, all of the debt is backed by Southern Water’s cashflow-generating assets. In effect, it securitises and tranches Southern Water’s future cash flows. Southern Water’s corporate structure is a massive CDO.

A very highly leveraged CDO, too. The equity slice is tiny, as this table from the 2023-24 annual accounts shows:

There is not much of a buffer here to prevent creditors taking losses.

How bad could creditors’ losses be?

When the CDOs failed in the financial crisis, losses cascaded all the way down to the super-senior securities. This was because issuers had used insurance contracts (“credit default swaps”) to offload the risk. Far more of these insurance contracts existed than there were assets available to meet claims. So the same aassets had effectively been mortgaged multiple times. Clearly, when there are multiple claims on the same asset, nearly all investors will take losses.

There doesn’t seem to be a similar derivatives edifice here. Southern Water does use interest rate swaps to reduce interest rate risk on fixed-rate debt, but I can’t find any evidence of synthetic derivatives being used to increase leverage. Mind you, this is an extremely complex structure, so I might have missed something.

But this doesn’t mean creditors are safe. The debt held in the Holdco and Midco groups is serviced entirely by transfers from the operating company. If those transfers fail, Holdco and Midco can’t pay their debts.

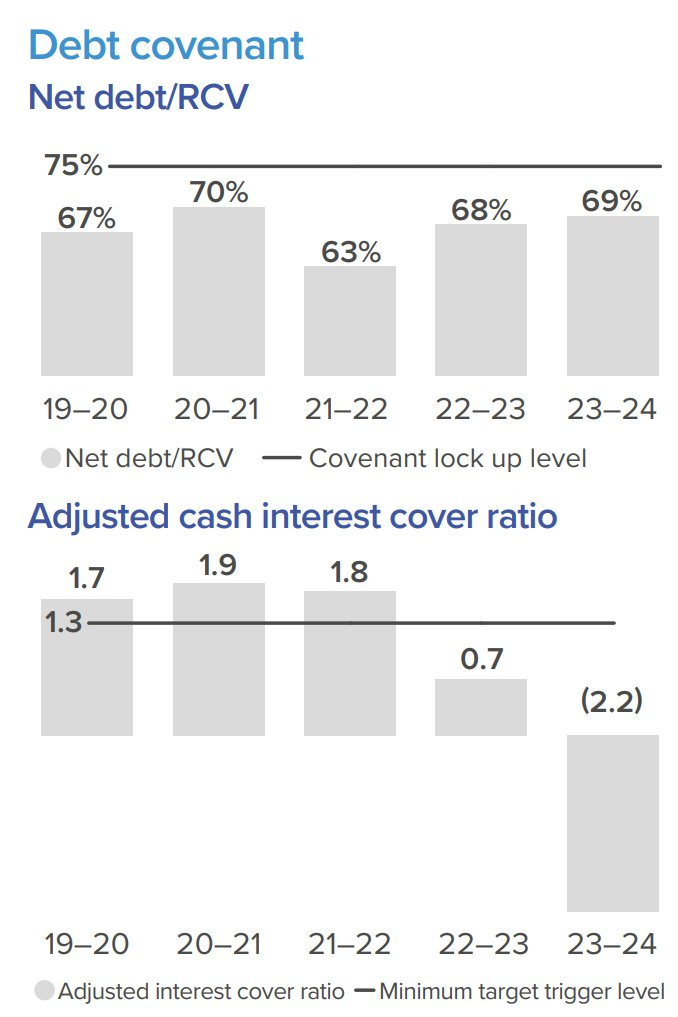

And the transfers have already failed. In fact they failed over a year ago. Southern Water’s “Common Terms Agreement,” under which its financing SPV, SW (Finance) 1 plc, issues bonds, includes what it calls “precautionary ‘early warning’ limits”, also known as Trigger Events or cash lock-ups, which prevent it paying dividends if it fails to meet certain predetermined criteria. In July 2023, Southern Water breached two of these criteria:

Following publication of our compliance reporting in July 2023, where interest cover was reported below its Trigger Event threshold, in addition to a downgrade by Fitch Ratings at the same time, the company entered a Trigger Event.

Southern Water opco was forced to stop paying dividends to its holding company. Holdco and Midco have been starved of money ever since. The 2023 accounts for all the companies in these groups contain “going concern” warnings.

In theory, creditors at this level could lose their entire investment. However, the bonds are backed by Southern Water’s cashflow-generating assets. If these companies were to default, there could be a swathe of court cases to try to recover the money from Southern Water.

But they haven’t - yet.

Why haven’t Holdco and Midco defaulted?

Partly, this is because they have cash reserves, built up through their practice of charging higher interest rates on intercompany loans than they pay on intercompany borrowings (the financial shenanigans in this structure are really quite something.)

They also have lines of credit with banks. Quite why banks are willing to lend to companies that have no income and no means of paying their debts is something of a mystery - though the fact that the companies’ ultimate source of cash is a too-important-to-fail public utility might have something to do with it. Banks really do like implied sovereign guarantees.

But the main reason why Holdco and Midco are still afloat is what in banking terminology we would call a “capital raise”.

In October 2023, Greensands’ principal shareholder, Macquarie (yes, the same “vampire kangaroo” that sucked Thames Water dry and sold the empty husk to unsuspecting pension funds) injected £550m of new equity into the conglomerate, increasing its total shareholding to 82%. You’d think this would go into new investment, wouldn’t you? But no. It went to service existing debt. Holdco received £100m of the new money and Midco £75m. And the remaining £375m went to service Southern Water’s own debts. For - in case you hadn’t noticed - it was Southern Water itself, not Holdco and Midco, that had breached a debt covenant and been subjected to a credit rating downgrade. Creditors can lose money at all levels in this structure.

The real debt mountain

Southern Water’s financing group has external debt totalling some £783m, dwarfing the debt in the Holdco and Midco groups. In 2023, its interest cover ratio, which means the amount of cash it is generating relative to the amount of interest it must pay, was 0.7, some distance below the minimum needed to meet its interest cover debt covenant. By the time the 2024 full-year accounts were produced, the ratio had turned significantly negative:

In short, Southern Water isn’t generating anything like enough cash to pay the interest on its debts. The only reason it hasn’t defaulted is that its principal shareholder has given it a substantial lump sum. When that money runs out - and it will, within the next few months - what happens then?

Brinkmanship

Southern Water cheerfully says it expects to come out of the cash lock-up in March 2025. But its plans depend on Ofwat agreeing to substantial increases in customer bills. And so far, Ofwat is not playing.

In July 2024, Moody’s put Southern Water on downgrade watch, saying that Ofwat’s refusal to allow Southern Water to increase prices by as much as it says it needs to restore it to financial health would:

…result in severe Outcome Delivery Incentive (ODI) penalties and total expenditure (totex) allowances below the level needed to fund Southern Water's investment programme…such under-performance may challenge the company's ability to raise equity finance to maintain leverage at levels consistent with the current rating.

In plain English, this means Southern Water would incur heavy fines for failing to meet regulatory standards, and would also be unable to make the investment needed to meet those standards. And its shareholders would balk at putting in any more money to enable it to service its debts.

Ofwat, of course, disagrees. It thinks Southern Water can meet its regulatory standards with lower customer bills and less investment. And it thinks investors should accept a lower rate of return.

It remains to be seen whether Ofwat or Southern Water will blink first. I suspect that, faced with the threat of a disorderly debt default and distressed nationalisation, the regulator may cave.

But neither side is addressing the real issue.

The elephant in the reservoir

There can be no private sector solution to the financial crisis engulfing Southern Water that does not involve very large increases in customer bills.

Water companies provide a finite resource to a restricted population. Their revenue comes almost entirely from customer payments. In such a business model, there are only two ways of generating more revenue: higher consumption, or higher prices.

Higher consumption is limited by supply constraints. If customers use more water and produce more waste, that puts strain on the supply of water and sewerage services. Investment in reservoirs, piping and sewerage treatment can mitigate (though not eliminate) supply constraints over the long term, but despite the massive levels of debt incurred by the water companies, water infrastructure investment has been inadequate for decades.

In a free market, when higher consumption is restricted by supply constraints, prices naturally rise. But Ofwat controls the prices water companies can charge. And for a long time, Ofwat regarded its principal job as being to keep customer bills low, not to ensure the long-term sustainability of the system.

When revenue growth through higher consumption is constrained, delivering high returns for shareholders while keeping prices low necessarily means rising debt and inadequate investment. Companies take on debt not to invest for the future, but to keep the ship afloat for as long as possible.

But now, the ship is visibly sinking. Water companies are unable to support existing levels of consumption, let alone plan for future increases. That’s why raw sewage is being discharged into waterways and the sea. That’s why households are experiencing water service interruptions, and hosepipe bans and other restrictions have become routine.

And because they have relied on debt to close the gap between the returns expected by shareholders and the prices they can charge customers, water companies like Southern Water are leveraged to the skies and flirting with debt default. Southern Water is currently unable to service its debts without equity injections. And its shareholder base is so thin that it is hard to see how it can raise much more from its shareholders, especially when they are faced with very low returns and no dividends for the foreseeable future.

I am frankly astonished that anyone ever thought this was a sensible business model for an essential utility. And I do not see why it has to continue. This experiment with private provision of a public service has failed, disastrously.

It’s time to do to the water companies what is already being done to rail operators. Nationalise them.

Related reading:

It begs questions about the accountants who advised and helped SW. Not unlike the lawyers advising the PO over Horizon and showed a similar lack of ethics. Tackling the advisors to companies - accountants, lawyers, bankers - gets towards the roots of the problems.

Thank you Frances, an excellent piece.