Thames Water is broke. Back in March, its existing shareholders refused to cough up any more money, saying it was “uninvestible”. In April, its parent company Kemble Finance defaulted on its debts. And in July, Thames Water admitted it had a maximum of 12 months’ liquidity left and would struggle to raise any more without an injection of new equity.

Thames Water presents this as a liquidity crisis: “if only someone will give us more money, we will be able to turn ourselves around and everything will be fine.” But regular readers of this blog will know that liquidity crises usually conceal a deeper, and potentially terminal, insolvency. In my view, that is the case here. Unless Thames Water can attract significant new equity investment, it is going down.

The day before the shareholders declined to contribute the additional £750m on which Thames Water had been counting, Thames Water paid some £1.5bn in dividends. This was in addition to interim dividends totalling £37.5m paid in October 2023. Thames Water has forked out nearly £2bn in dividends in the last financial year. That sounds like a good windfall for shareholders, doesn’t it? So why wouldn’t they give the company the money it needed? They must be sharks, the lot of them. Vampires. Bloodsuckers.

But the 2023-4 accounts reveal that the shareholders didn’t get a penny of those dividends. In fact they have not received a dividend since 2017.

So where did the money go?

Thames Water’s complex corporate structure

Thames Water is not a single company. It is a complex conglomerate with some extremely opaque - some might say incomprehensible - structures. Here’s Thames Water’s own diagram of its corporate structure:

Note where the shareholders sit. They are shareholders of Thames Water’s ultimate parent Kemble Water Holdings Limited (KWHL), not Thames Water Limited (TWL) or any part of it. And the multiple layers of ownership below KWHL create plenty of opportunity for money to vanish before it gets anywhere near shareholders. So maybe the shareholders aren’t sharks or vampires. Maybe they, too, are victims.

The too-important-to-fail regulated utility is Thames Water Utilities Limited (TWUL), which sits within the “Whole Business Securitisation Group” and is two levels of ownership down from Thames Water Limited. The other companies in the securitisation group are a financing vehicle, Thames Water Utilities Finance plc (TWUF), and a holding company, Thames Water Utilities Holdings Limited (TWUHL), of which more shortly.

What is a “whole business securitisation group” and why does it matter?

Whole business securitisations (WBS) have become popular ways of raising money from a business’s future cash flows. In a traditional mortgage securitisation, a bank issues securities backed by packages of mortgages: the cash flows from the mortgages flow to the holders of the securities in the form of debt service. WBS works similarly, but the backing assets are the business’s future cash flows, including uncertain and contingent ones.

Tranching creates different classes of security: losses are felt first by the holders of the riskiest securities (the “equity” tranche) then cascade down the risk classes. So, even if cash flows severely disappoint, the holders of the “safest” tranches are usually protected from losses. These tranches typically have investment grade credit ratings, so attract risk-averse investors such as pension funds. Since WBS cash flows are uncertain, it’s usual for WBS securities offerings to be tranched.

Just like mortgage-backed securities, a WBS group usually includes a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to separate the securitisation engine from the operational entity. For Thames Water’s WBS, this is TWUF. It is a wholly-owned subsidiary of TWUL which exists solely to securitise TWUL’s cash flows. There’s also an offshore (Cayman Islands) SPV outside the WBS structure.

And what is the purpose of the holding company? Why, it’s to minimise tax. This is how it works:

TWUF securitises TWUL’s future cash flows and sells the securities to investors, both in the capital markets and as private placements

TWUF lends the money it receives in return for securities sales to TWUL at a margin over the coupon rate on the securities

TWUL on-lends this money to its parent TWUHL at a margin over the rate it pays to TWUF

TWUHL has no commercial activities and no income of its own. So to enable it to service its debt to TWUL, TWUL pays it dividends. These dividends are TWUHL’s only income

The dividends paid by TWUL are sufficient to service the debt TWUHL owes to TWUL, but not to service the debt loaded onto TWUHL by its parent Thames Water Limited. So TWUHL makes a substantial loss every year, on which it receives tax relief. It shares this relief with the other companies in the WBS group - and, as we shall see, also with companies higher in the structure - thus reducing Thames Water’s overall tax liability.

I know this sounds incredible, but the evidence is in TWUHL’s accounts (these are for the 2022-3 financial year as TWUHL has not yet produced its 2023-4 accounts):

(the “direct subsidary undertaking” is TWUL).

The three companies in the WBS all guarantee each other’s debts, and also collectively guarantee securities issued by TWUF and TWUF Cayman. This “all for one, one for all” relationship ring-fences the three companies from the superstructure built on top of them and insulates them from financial distress elsewhere in the conglomerate.

Why do the Kemble companies exist?

The Three Musketeers - TWUHL, TWUL and TWUF - together constitute a self-contained and self-sustaining group. They raise their own finance, move money around within their own structure, and maintain their own debt covenants and guarantees. The heart of this group is the regulated utility with its stable cash flows from an enormous captive audience of retail and business customers. There seems no reason for the rest of the conglomerate to exist. So why does it?

To find out why the Kemble companies exist, we need to look back to 2006, when the German utility company RWE sold Thames Water to a consortium led by the Australian investment bank Macquarie Group. The consortium created KWHL to hold shares in the group, and the other Kemble companies to hold the debt the consortium took on to buy the company. Thames Water Limited (TWL), the original listed company created in the 1989 privatisation, became a wholly-owned subsidiary of Kemble Water Finance Limited (KWFL). There’s also an SPV, Thames Water (Kemble) Finance Limited (TWKFL), which exists to raise debt finance for the Kemble group of companies.[1]

The Thames Water conglomerate thus consists of two corporate structures; Thames Water WBS, in which is embedded the regulated utility on which thousands of people depend, and the Kemble group of companies. Thames Water WBS is self-contained - but the Kemble structure is not. Not one of the companies in the structure does any productive activity. They are purely financing vehicles and holding companies. They survive by sucking cash from Thames Water Utilities Limited, the only operating company in the conglomerate. If that vein is severed, the Kemble structure dies.

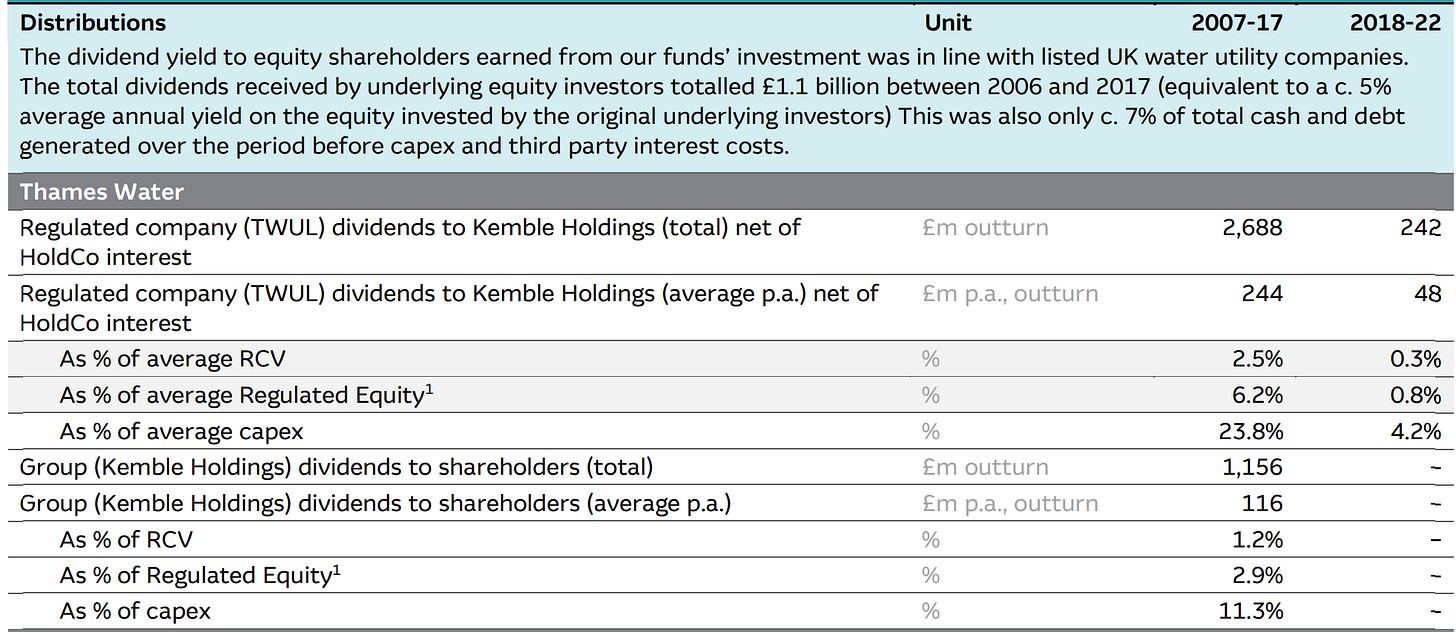

During Macquarie’s ten-year ownership, the parasitic Kemble group leeched an astonishing £2.7bn from the regulated utility. Of this, according to Macquarie, £1.1 bn went to shareholders, mostly (£879m) in the form of dividends: the rest went into debt service. Macquarie’s own investment funds received nearly half (£508m) of the distribution to shareholders.

Macquarie gradually reduced its stake in Kemble from 2012 onwards. On 14th March 2017, it sold out completely.

The current shareholders are a group of public sector pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and other investment funds. The two largest investors, by far, are Canada’s Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement Scheme, which holds 31.777% of the shares, and the UK’s Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), which holds 19.711%.

With the departure of Macquarie, distributions to shareholders stopped. The drop-off in dividend payments after Macquarie’s exit is painfully evident in Macquarie’s table above. Not for nothing is it known as the “Vampire Kangaroo”. The current shareholders have never received a penny in dividends.

But the leeching didn’t stop. Owning shares is not the only way of extracting cash from a privatised utility. Lending it money works equally well - until the regulator puts a stop to it.

Debt as an extractive tool

A BBC investigation in 2023 revealed that £2bn of Macquarie’s acquisition cost of £2.8bn had been loaded on to TWULH’s balance sheet and refinanced with bonds issued by TWUF Cayman (these bonds were later novated to TWUF). TWULH is paying 10% interest on this debt:

Now, this isn’t a real cash transfer. It’s an accounting sleight of hand, the effect of which is to create a perpetual tax loss, thus enabling Thames Water to reduce its overall corporation tax liability through a scheme known as “group relief” which enables profits in one entity to be offset by losses in another [2]. The real debt service payments flow from TWUL to TWUF, and thence to bondholders.

But the £2bn acquisition cost is only a small part of Thames Water’s total debt. During Macquarie’s ten-year ownership, total external debt rose from £3.6bn to £10.8bn. And it has continued to rise since Macquarie sold out. Today, Thames Water’s net debt stands at nearly £18bn.

Thames Water’s WBS has gross external debts of £16.4bn, of which £1.3bn are subordinated (Class B). That’s high, but at least the WBS includes an opco capable of generating the cash flows to service the debt.

The Kemble structure has no opco - and yet it too has external debt. KWFL and its SPV between them have gross external debt of £1.35bn, all of which must be repaid by 2028. And KWFL’s parent, Kemble Water Eurobond plc (KWE) holds about £1bn of shareholders’ loans. To service this external debt - including the shareholders’ loans, which unlike dividends are an obligation - the Kemble companies must receive actual cash transfers from TWUL. Accounting tricks won’t satisfy external investors.

And that’s where those controversial dividend payments come in. Well, part of them, anyway. TWUL has for years been paying dividends to Kemble to enable it to service its debts. Guess who one of the beneficiaries is? Yes, it’s Macquarie. About 9% of Kemble’s debts are owed to the Australian vampire.

In 2021-2, TWUL paid £37m in dividends to Kemble for debt service. Kemble’s actual debt service cost that year was £67m, but it covered the difference from “cash reserves” - which as the conglomerate is so highly indebted, in reality means borrowing. Borrowing to service existing debt is known as ponzi finance and is unsustainable.

The funny-money dividends

All dividends paid by TWUL go, in the first instance, to TWUHL as TWUL’s immediate parent. This is an intercompany transfer within the WBS. The question is what happens next.

Here’s the breakdown of the nearly £2bn dividend paid in 2023-4.

The interim dividend of £37.5m paid in October 2023 was distributed by TWUHL to TWL, which passed it on to KWFL. KWFL used the dividend to service its and TWKFL’s external debt obligations.

The transfer to KWFL was the only real money paid out. The rest of the “dividend” was accounting shenanigans.

£27.1m went to top up Thames Water’s two defined benefit pensions:

In March 2024, Kemble Water Eurobond plc (“KWE”), an intermediate parent of the Company, made internal inflation mechanism pension contribution payments totalling £27.1 million to the defined benefit schemes, Thames Water Pension Scheme and Thames Water Mirror Image Pension Scheme, on behalf of the Company. In connection with this transaction, the Company issued 27.1 million shares with a nominal value of £1 each to TWUHL, for a total value of £27.1 million. The Company paid a £27.1 million dividend to TWUHL and through further intercompany transactions between intermediate holding companies, the amount was to be received by KWE. These flows were settled cash neutrally as part of a net settlement deed, and as a result of this arrangement, £27.1 million was paid directly into the defined benefit pension schemes.

This complex piece of accounting requires some explanation. Thames Water’s main DB pension fund has a deficit which in 2019 amounted to some £150m, while its secondary DB fund (“Mirror Image”) has a surplus of about £33m. Both are, however, affected by higher inflation, since the value of investments falls when inflation is high. Thames Water has for some years now been making additional contributions to its main fund to close the deficit. And in 2023-4, it also made contributions to both funds to compensate them for losses due to higher inflation. These payments were made from KWE’s capital (not cash) reserves [3], which in the 2022-3 accounts (the latest available) stood at nearly £4bn. The dividend payment from TWUL to KWE (via TWL and KWFL) partially replenished those reserves. No cash movement was involved.

The remainder of the dividend, some £131m, was retained by TWUHL and netted off against transfers from other companies:

In March 2024, the Company paid dividends of £131.2 million to TWUHL. Simultaneously the Company received payments for group relief owed by TWL, TWUF and KWE totalling £153.6 million and settled intercompany loans including associated interest owed to TWUHL (£5.6 million), TWL (£0.3 million) and TWUF (£16.3 million). These, along with other intercompany transactions between other group companies were recorded under a net settlement deed, and as a result no cash payments were made by the Company in connection with the £131.2 million dividends.

I’ve already noted the circularity of the relationships in the WBS. This is a fine example of how money is also shifted around within the wider group to minimise tax liabilities.[2]

Downward spiral

Macquarie claims to have invested £11bn in Thames Water, but it’s painfully evident that this was not its own money. The accounts show a continual cash drain from the company to Macquarie’s funds, accompanied by a massive increase in debt. Macquarie’s exit in March 2017 reduced the bleeding, but the company was already entering a downwards spiral.

A week after Macquarie sold its remaining stake, Thames Water was hit with a fine of over £20m for repeated pollution incidents in the River Thames between 2012 and 2014. There have been further fines since, and there are more to come.

Repeated regulatory fines are a contributory factor in Thames Water’s financial distress. But despite shareholders’ complaints, they are not the sole, or even the main, cause. The real issue is that the complex extractive structure set up by Macquarie is, and always was, unsustainable.

Embedding a regulated utility with a captive customer base in an extractive capital structure looks like a free lunch. No wonder these structures are so prevalent. But free lunches have hidden costs. In the case of Thames Water, the hidden cost is environmental - and political. Captive they may be, but Thames Water’s customers can’t be fleeced with impunity. They are are horrified by the stinking mess that water companies have made of the UK’s rivers, and furious at Thames Water’s suggestion that they should have to pay far higher bills to fix the problem.

On 11th July, Ofwat refused to allow Thames Water to raise customer bills by the amount it said it needed to fix its dire liquidity shortage and attract new investment. Deeming Thames Water’s business plan “unsatisfactory”, it placed the company into a “turnaround oversight regime” and said it would be subject to “heightened regulatory measures”.

To what extent this decision was driven by the political storm around Thames Water’s awful performance, we don’t know. But it had a disastrous effect on Thames Water. The ratings agencies S&P and Moody’s downgraded its credit rating to junk. As a result it is now in breach of its operating licence. The likelihood of attracting new equity investment is rapidly diminishing - yet without it, the company cannot obtain more liquidity.

Thames Water says it has enough liqudity to survive until May 2025, but liquidity that consists of bank loans and revolving credit facilities has a way of drying up much more rapidly than companies expect. In 2018, the outsourcer Carillion collapsed after the UK bank RBS told it to pre-fund all payments to suppliers. Like Thames Water, Carillion had insisted its problem was liquidity: but it was actually so deeply insolvent that it went straight into liquidation and its creditors, including numerous small suppliers, lost their money.

A similar implosion of the Kemble structure looks inevitable to me. And one at least of its shareholders thinks so too. In July, USS, Kemble’s second largest shareholder, wrote down the value of its stake to zero.

In the event of Kemble’s insolvency, the unfortunate shareholders who were sold a pup by Macquarie would all be wiped. The question is whether, and to what extent, Kemble’s creditors would also take losses. Since Kemble has no cash-earning assets of its own, and Thames Water’s WBS is ring-fenced, it is hard to see how Kemble’s creditors could recover anything either.

Kemble currently channels equity and some debt finance to Thames Water. But in the notes to the 2023-4 accounts, Thames Water observes that if the Kemble superstructure could no longer be used for financing, new equity could be injected directly into the WBS. So Kemble can be allowed to collapse without threatening Thames Water’s ability to deliver services to its customers.

But it’s not just Kemble that is struggling. Thames Water itself is over-indebted, seriously short of liquidity, and desperately in need of considerable investment. This is the real problem that the regulator - and perhaps also the government - must address.

Some kind of resolution for Thames Water seems likely, and it will have to involve elimination of a considerable part of that debt pile to clear the way for new investment and liquidity facilities. TWUF’s subordinated bonds can be wiped - their credit ratings now reflect this. But most of the creditors are senior. They would not take kindly to a haircut.

However, it seems unlikely that prospective investors would be willing to take on so much debt, and the government taking it on would be incredibly unpopular. So perhaps the way forward will be to convert Thames Water’s senior debt to equity - though the resulting lawsuits could last for years.

A new settlement

Going forward, a new settlement is needed for privatised utilities. Many people would like them to be taken back into public ownership. This would be extremely expensive, but it perhaps offers the best prospects for customers and the environment.

But if they are to remain in the private sector, then in my view they should be subject to the same sort of regulation as the PRA imposes on banks. Capital requirements, liquidity requirements, leverage ratios, simple corporate structures (Revolut had to simplify its corporate structure in order to qualify for a banking licence), robust risk and compliance frameworks, approval regimes for senior management, resolution plans.

No longer must regulated utilities be the victims of vampires.

Related reading:

Clearing out Carillion’s cupboards

Image of the River Thames is from Wikipedia.

Notes

The structure above KWFL was a good deal more complicated during Macquarie’s ownership, but it was simplified in 2019.

From Thames Water’s 2024 tax strategy document (my emphasis):

“Thames Water does not currently pay corporation tax because of the Government’s capital allowances regime, and the impact of our interest costs. The capital allowances rules encourage capital investment in infrastructure and effectively defers the time at which corporation tax is paid. Interest costs are deductible for tax purposes and are substantial at the moment. Importantly, our customers benefit from our current corporation tax payment position as the reduced cost is fully passed on to customers through lower bills, reflecting the current regulatory model for the water sector.”Thames Water says it does not engage in “aggressive tax avoidance”, but its egregious use of intercompany transfers to reduce corporation tax liability to near zero looks pretty aggressive to me.

KWE’s capital reserves are more funny money. They emerged in 2007, the first year of KWE’s operation, as a result of the total debt owed to KWE by its string of subsidiaries exceeding the debt KWE owed to KWHL by some £5bn. But intercompany debts, and the interest charged on them, are entirely a management choice. Thames Water’s management wanted KWE to hold capital reserves on behalf of the Group, so they established intercompany loans between the various entities so as to generate the desired reserves. The reserves are labelled as “retained earnings” in KWE’s accounts, but as KWE doesn’t earn anything, this is misleading to say the least.

The financing of the pension contribution with further debt against new equity issued to TWUHL is an insult to investors. Capital has been offered to the trustees so that an SLP can co-sponsor the two pension schemes. This would enable the pension schemes to run on without troubling its sponsor with further demands. The SLP would enable the pension fund to pay pensions in full. For some reason, the trustee has decided not to enter into discussions on this offer.

I see PWC are their auditors. Must have generated considerable fees to PWC or their predecessors, setting up all these arrangements. Begs a question about the ethics of auditors, not dissimilar to the ethics of the lawyers advising the Post office over the Horizon scandal.

The sheer length and number of the notes to the accounts says an awful lot...

In this and other sectors there are difficult questions over whether regulators can ever be sufficiently effective given the legal and financial firepower of those they are trying to regulate and the risk of regulatory capture. Utilities, finance, tech and Boeing come to mind.