The "deserving poor" are the latest target of Government cuts

Sick and disabled people do not deserve the harsh treatment the Government has planned for them.

For over half a century, the prevailing view in British politics has been that people who are unable to work because of sickness or disability are more deserving of public support than those who are unemployed. The fit and able can be forced to work by cutting unemployment benefits to poverty level, but treating with such harshness those who, through no fault of their own, are unable to work is unfair, unjust and, most importantly of all, unpopular.

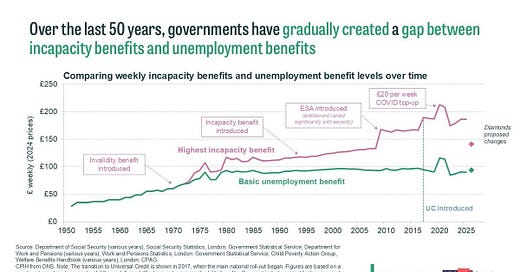

The widening gap between incapacity benefits and unemployment benefits reflects this distinction between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor:

(chart from the IFS)

The “undeserving” poor have had a pretty rough time. Unemployment benefits have not risen in real terms since 1979, except for the temporary top-up during Covid which was removed in 2022. During the 1980s and 1990s they rose in line with inflation, and although they were frozen during the 2010s, there wasn’t any inflation to speak of, so their real-terms value was more-or-less maintained. But the inflation surge of the early 2020s ended this. The real value of unemployment benefits fell sharply after Covid and remained lower than at any time since 1980. And it is even lower for young people.

Now, for the first time in decades, that is about to change. In its Spring review, the Labour government announced a real-terms increase in the basic rate of Universal Credit. This will restore it to about half of its 2010 value:

(chart from the Resolution Foundation)

It’s still far below the level of other state benefits, notably the state pension (which is ratcheting ever upwards because of the triple lock). But this nevertheless reflects a change in attitude towards the unemployed, particularly young people. They aren’t quite as undeserving as they used to be.

On the other side of the equation, harsh cuts to incapacity benefits are planned. The sick and disabled are nowhere near as deserving as they used to be.

A fundamental policy change

The IFS says this represents a fundamental change to the way that the state supports out-of-work people:

At its core, the decision is to tilt the welfare system away from those who are disabled and towards those who are unemployed without an assessed disability.

It’s a very considerable tilt, too. These indicative examples from the Resolution Foundation show that some people’s annual income will drop by thousands of pounds:

If you are out of work but not sick or disabled, you’ll get more money. If you are disabled, you’ll get less, whether or not you are working. And if you are unable to work because you are sick but not disabled, you’ll get nothing.

The “undeserving poor” are now those who are physically or mentally incapable of working.

Except, that is, for the largest group of non-workers. State pensioners remain “deserving” whether or not they are capable of work. Indeed, an increasing number are working:

(chart from ONS)

Of course, the rising state pension age reduces the number of fit and healthy state pensioners. But it also increases the number of working-age people with health problems and disabilities severe enough to prevent them from working. The glaring unfairness of forcing someone of 65 who is unable to work because of crippling arthritis to live in abject poverty while someone only a year older, who has no significant health problems and is continuing to work, receives a full state pension seems lost on policymakers.

Everyone can work

The Government’s Green Paper complains that the benefits system:

is built around a fixed “can-versus-can’t work” divide which does not reflect the variety of jobs, the reality of fluctuating health conditions, or the potential for people to expand what they can do, with the right support.

It aims to scrap this divide:

Our objective is to ensure more disabled people and people with health conditions are able to work and get the benefits bill onto a more sustainable footing.

This would reverse the policies not merely of the last 60 years, but the last 600. Since mediaeval times, it has been generally accepted that the old, the ill, the infirm, children, heavily pregnant women and new mothers should not be expected to work. The modern welfare state was built on the principle that working people would, through their taxes, support those unable to work because of age, sickness, disability or maternity.

But although it sounds simple to distinguish between those who can work and those who can’t, it has never been reliably achievable in practice. Policy has swung wildly between compassionate and draconian. For example, under the Poor Laws of Elizabethan times and thereafter, infirmaries and orphanages sprang up to care for people too old, too young, too sick or too infirm to work: but in the 19th century, ideological belief in the virtue of work, coupled with worries about the rising cost of supporting people who, for whatever reason, were not working, led to a disastrous experiment with forcing everyone to work. Public outrage at harsh workhouse regimes eventually led to the introduction of the state pension in 1908 and the abolition of workhouses in 1930.

Governments have - for now - largely stopped trying to force children and the elderly to work. But sick and disabled people are a perennial target. Successive governments have implemented measures to force them to work, with little effect other than to increase misery. In 2019, the National Audit Office sharply criticised the (then) government’s approach to improving access to work for disabled people, saying that the government simply did not know whether its policies - or for that matter, the policies of previous governments - worked:

Given the Department has had programmes in place to support disabled people for over half a century, it is disappointing that it is not further ahead in knowing what works and that it lacks a target that it is willing to be held to account for. While the commitment to gathering evidence is welcome, until it has a clear understanding of what works, and a plan to use that evidence, it is not possible to say the Department is achieving value for money.

In nearly sixty years, no-one has managed to show that driving a wedge between “deserving” and “undeserving” benefit recipients increases the labour force participation of sick and disabled people. So perhaps scrapping this distinction is not such a bad idea. The Government’s vision seems attractive:

Disabled people and people with health conditions, who are able to, should have the same access to opportunities, choices and chances as everyone else. That is what we mean by an equal society. Many disabled people and people with health conditions want to work but are not supported to do so.

But despite its fine words, the Government isn’t really scrapping the “can-versus-can’t-work” divide. It’s just changing the definition. The final point of its five-point manifesto for disabled people says:

We will protect disabled people who can’t and won’t ever be able to work and support them to live with dignity.

Not everyone can work. There will always have to be an assessment process to determine who “deserves” to be supported without work requirements and who does not. Tellingly, the Green Paper does not attempt to define what support would be provided to those unable to work, nor even how they would be identified. The “deserving” and “undeserving” divide is as contentious as ever.

What is the government’s real objective?

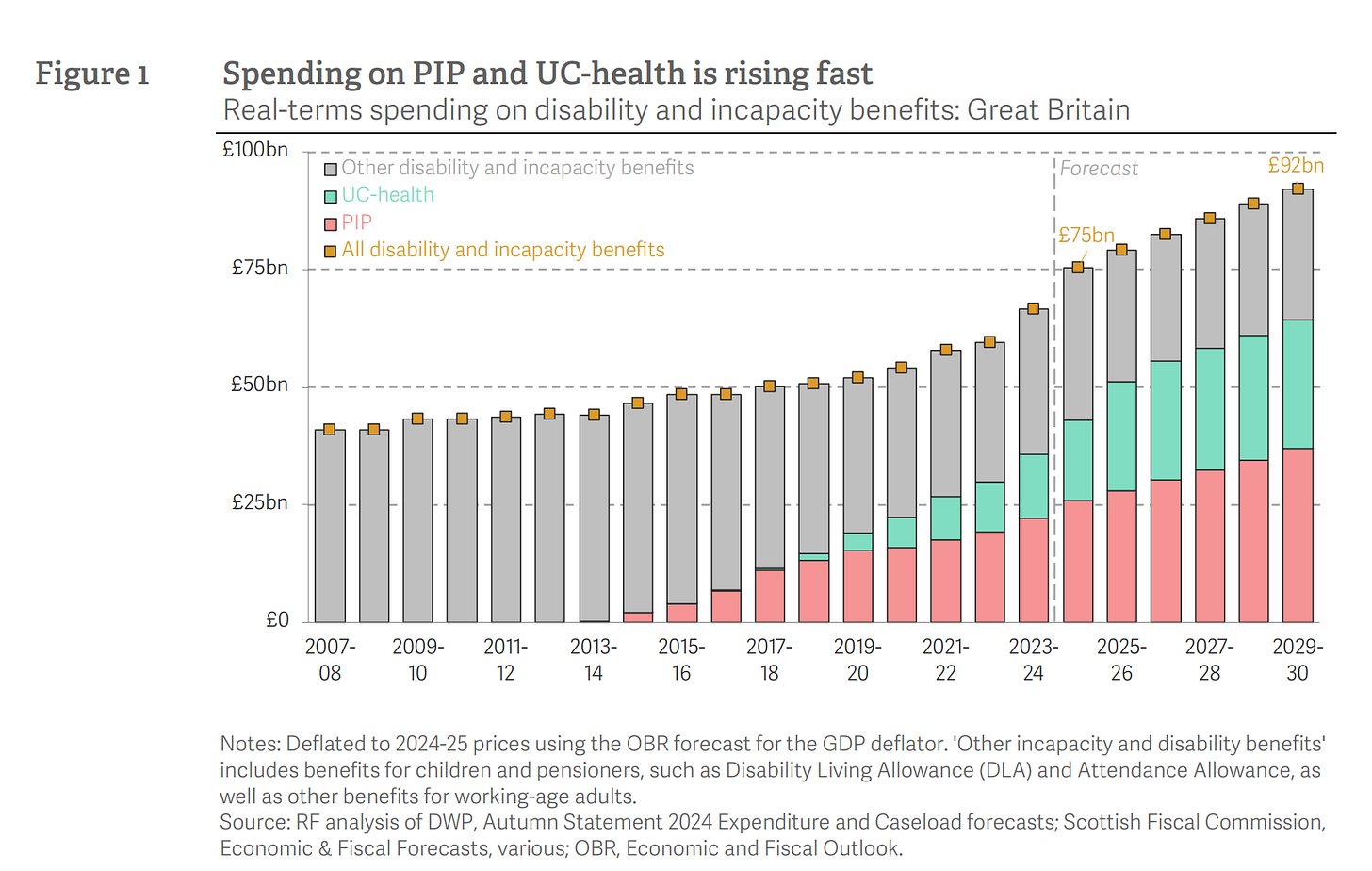

It’s not difficult to see why the government is desperate to reduce benefit payments to the sick and disabled. Government expenditure on incapacity and disability benefits is rising rapidly. The principal contributors to this increase are the health-related element of Universal Credit (which roughly equates to what used to be known as “incapacity benefit”) and the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) that compensates recipients for the additional costs of living with disabilities:

(chart from the Resolution Foundation)

The first chart in this piece shows that harsh treatment of the “undeserving poor” and relatively generous treatment of the “deserving poor” over the last half-century has created a large and growing wedge between out-of-work benefits and incapacity benefits. In particular, the introduction of ESA in 2008 significantly increased the benefits paid to sick and disabled people, while the benefits paid to the able-bodied unemployed stagnated. It also increased the cost to the Exchequer of incapacity benefits.

The Work Capacity Assessment (WCA) process introduced at the same time as ESA determines whether or not someone qualifies for incapacity benefits (ESA or health-related UC). People deemed to be “fit for work” (FFW) are expected to look for work. Those deemed to have “limited capability for work” (LCW) are expected to become capable of working in the near future, and are therefore expected to participate in “work-related activity”, such as meeting with job coaches. Both these groups receive unemployment benefits rather than incapacity benefits, and are subject to sanctions if they fail to participate in job search or work-related activity.

In contrast, those who are deemed to have “limited capability for work and work-related activity” (LCWRA) are not expected to become capable of working in the foreseeable future. They receive a higher level of benefits, are not required to look for work or participate in work-related activity, and are not subject to sanctions.

In response to the rising cost of incapacity benefits and public anger over “scroungers and shirkers”, the Coalition and Conservative governments set up a vast, inefficient and brutal WCA administration whose entire purpose appeared to be to make claiming benefits as difficult as possible for sick and disabled people. But extra bureaucracy and harsher conditionality did not reduce the benefits bill. The total cost of incapacity benefits (ESA and US) has not changed much since 2010. The chart above appears to show that claims for the health-related element of Universal Credit are rising extremely rapidly. But this is an illusion. UC-health is replacing means-tested ESA. As ESA reduces (grey bars), UC-health necessarily increases.

The biggest rise in disability-related benefits - and hence the biggest headache for the Treasury - actually stems from PIP.

Unlike ESA and health-related UC, PIP is not an out-of-work benefit. It is paid irrespective of whether the recipient is working, and is intended to relieve the additional costs of living with a disability.

PIP is a popular benefit: since its introduction in 2013, claims have continually increased. Many disabled people say PIP helps them to work, since they can use it to pay for, inter alia, mobility aids, communication aids and transport. But is unclear to what extent PIP increases the number of disabled people who are in work - and more importantly, reduces the number who are not.

From the Treasury’s perspective, rising PIP costs need to be brought under control. And mindful of the NAO’s criticism, the Treasury also wants to show that PIP delivers value for money.

The Government’s proposed changes to the benefits system for sick and disabled people therefore aim to cut not only the cost of supporting people currently deemed unable to work, but also the cost of enabling sick and disabled people to live independent lives.

Perverse incentives

The fact that incapacity benefits are higher than unemployment benefits creates an incentive for people to claim incapacity benefits. Right-wing media and politicians have been particularly vociferous about this, but left-leaning thinktanks have reached similar conclusions. Here’s the Resolution Foundation, for example (my emphasis):

The changes to UC represent a redistribution of benefits away from the LCWRA element towards the standard allowance. We and others had previously pointed out that there are very large difference between these two rates (a single person receives more than twice as much UC if they are put in the LCWRA group) and that this creates a very large financial incentive for someone to get into the LCWRA group. The Government has responded to this with a dramatic set of changes: increasing the basic rate of UC by around £3 a week above inflation, but cutting the LCWRA for new claimants by over £50 per week relative to the usual inflation uprating.

The enormous wedge between unemployment and incapacity benefits means that sick and disabled people stand to lose a lot of money if they are deemed capable of work. And if they do work, this may affect their entitlement to benefits. The government hopes that slimming down the wedge between incapacity benefits and unemployment benefits will reduce the perverse incentive for sick and disabled people to prove they are incapable of doing any work at all.

But there are two ways of slimming down a wedge. The government could have raised unemployment benefits to their 2008 level. It has chosen instead to cut incapacity benefits to their 2008 level. Existing LCWRA recipients will have their payments frozen for four years, eroding their real-terms value. And from April 2026, payments for new claimants will be reduced by nearly half and also frozen for four years.

The increase in unemployment benefits is so small that it will be wiped out by inflation, while many sick and disabled people will face catastrophic falls in living standards. The stick long applied to the unemployed is now being applied to sick and disabled people, and the carrot is nowhere to be seen.

There seems no doubt that this decision stems from the government’s fiscal constraints. Raising unemployment benefits would have been a considerable cost, but cutting incapacity benefits might generate considerable savings. It is depressing that because of Treasury cost-cutting, measures billed as making the benefits system work better for sick and disabled people will, if enacted, cause severe harm to the the very people they are intended to help.

Undermining PIP

LCWRA is not the only benefit subject to Treasury cost-cutting. The government also proposes to tighten the qualifying criteria for PIP considerably, so that only people with severe disabilities would receive it. People with moderate disabilities that impair their quality of life would no longer receive it. This would significantly reduce the incomes of many disabled people. It could also make it impossible for some of them to work, which seems entirely counterproductive.

But perhaps the most draconian measure proposed is to tie together LCWRA and PIP. Currently, someone can qualify for LCWRA without claiming or receiving PIP. But the Government wants a successful PIP claim to be the gateway for LCWRA, thus eliminating the link between WCA and LCWRA. If this change is enacted, people in the LCWRA group who lost their PIP entitlement would also lose their health-related benefits. The Resolution Foundation’s indicative example for a single person currently on LCWRA (UC) and PIP estimates an annual income loss of £9,600. I have seen estimates of losses totalling £12,000 or more. These people are far from rich. Such massive cuts to their annual income would catapult them into absolute poverty.

Restricting PIP to severe disabilities only is an extremely short-sighted measure. It undermines the entire purpose of PIP, which is to ensure that people living with disabilities are not financially disadvantaged relative to people without disabilities. If this change is enacted, then people with disabilities will have to earn more than people without disabilities simply to achieve the same standard of living. It is hard to see how this is remotely compatible with the Green Paper’s fine vision of an equal society for everyone.

Think again

The rapid growth of distributed and online jobs could make it possible for more sick and disabled people to work. But we aren’t there yet. There are huge barriers to employment for many disabled people: for example, in 2024 the Buckland Review, citing the Labour Force Survey, reported that only 30% of autistic people are in employment, because job application processes are hard for many autistic people to navigate and autistic people often struggle to fit in to corporate cultures. And the growth of employment-destroying technology such as AI will inevitably diminish opportunities for disabled people, at least in the short to medium term.

The employment support measures in the Green Paper are welcome, but wholly inadequate. In the absence of major initiatives to tackle barriers to employment, including subtle discrimination by employers, the Government’s proposed changes would simply result in higher unemployment among sick and disabled people as more of them were deemed capable of work. And even for those who find work, the benefit cuts are likely to mean a vast increase in poverty.

Sick and disabled people do not deserve such harsh treatment. And the Green Paper’s vision of (almost) everyone working instead of living on benefits is pie in the sky. The Government must think again.

The figure for autistic people in employment has been corrected. An earlier edition said 70%, but this was the figure for autistic people NOT in employment.

Related reading:

Reforms to working age benefits - IFS

A dangerous road - Resolution Foundation

To add a little - since the Government's announcement, a range of informative information has been extracted by FoI as well as being included in successive 'evidence packs' from DWP. One of the most useful FoIs is https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/numbers_of_claimants_of_pip_who#incoming-2991716.

What this indicates is that, despite the Green Paper talking a lot about rises in claims amongst young people and claimants on grounds of mental health and of autism and ADHD, the incidence of people at risk of losing benefit is rather different - people aged 50+ and those with musculoskeletal conditions, with a higher proportion of women affected than men.

Notably, despite the last WASPI women (accepted as such by the campaign) ageing out of the workforce later this year, it's women who would, under the prior age 60 pension have a state pension, but have significant health issues and are now within the working age group, who seem worst affected.

The OBR thinks that welfare advisers and successful appeals will succeed in getting a lot of those affected through the new version of the test, as has previously been the case with successive attempts to tighten eligibility - the moves from Invalidity Benefit to Incapacity Benefit (the All Work Test) and from Incapacity Benefit to Employment & Support Allowance (Work Capability Assessment) both had this effect.

Also, Ben Baumberg Geiger (https://inequalities.substack.com/) has a lot of useful context.

"only 70% of autistic people are in employment, because job application processes are hard for many autistic people to navigate and autistic people often struggle to fit in to corporate cultures."

One of my friends, deeply Aspie, top 1% IQ, recounted to me how she could only find bottom of the barrel work in the UK as she simply couldn't get through the job interviews for anything more suitable to her undoubted abilities. Finding herself abroad (long story) she applied for quality work and breezed into it as well, doing it well enough to be able buy her own house after a time. This rather suggests to me that, as per bleedin' usual, it's British attitudes which are the problem, not any lack of ability on behalf of the people.