Tunnel economy

How a network of tunnels built for smuggling revitalised Gaza's economy and enabled it to withstand a siege.

“When you compare the size of Gaza to London,” says Eylon Levy, Israel’s spokesman, “it’s insane that Hamas built an underground military tunnel network reportedly 1.5 times the length of the Tube. Every shaft in a school, home, mosque, hospital, or UNRWA facility. So much wasted potential for Gaza under Hamas. For what?”

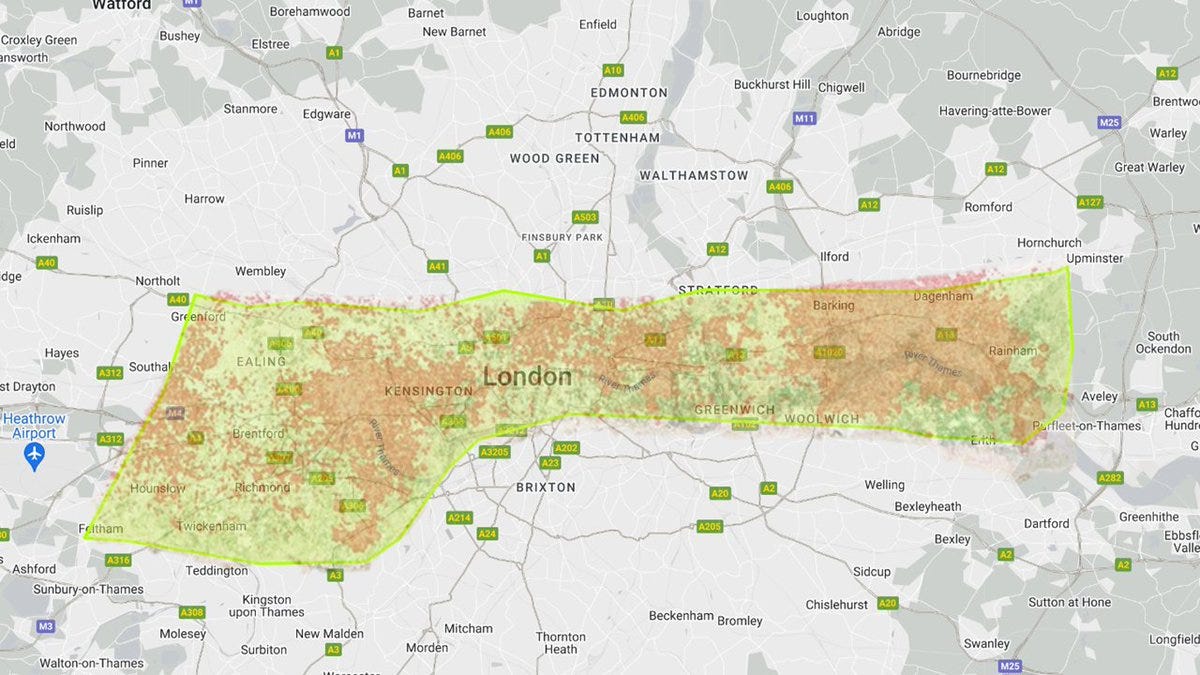

Levy is referring to this image superimposing Gaza on London, from Alonso Gurmendi, Lecturer in International Relations at Kings College London:

Yes, Gaza is tiny. Many people I’ve spoken to don’t realise how small it is. I recall one person telling me that Israel couldn’t possibly do a ground invasion of Rafah, at the extreme south of Gaza close to the Egyptian border, because it’s “too far from Israel.” Rafah is only about four miles (6.4 km) from the Israeli border.

London and Gaza

Gaza is also very densely populated, which largely explains the extraordinarily high casualties in Israel’s blitzkrieg. It is often said that Gaza is “the most densely populated place in the world.” And compared to whole countries, it is. The UK has one of the highest population densities in the world, at 270 people per square km. Gaza’s population density is 5,500 people per square km.

But this is a false comparison. Gaza isn’t a country, it is a city-state - or would be if it were formally recognised as such, rather than the no-mans-land it has been since Israel’s withdrawal in 2005. And when you compare it with other sprawling urban conurbations, its population density doesn’t look exceptional.

London’s population of 9.65m is more than three times larger than Gaza’s 2.3m. But as the image shows, it’s also considerably larger in area. So, on a population density basis, the two are comparable: London has 5,460 people per square km to Gaza’s 5,500.

Gurmandi comments that a similar blitzkrieg in London would destroy “all of Camden, Angel, Hammersmith, Barking, most of Kensington & Chelsea, Soho, and Woolwich, and half of Fulham.” But would it kill as many people? Probably not. And the reason is - tunnels.

London is underpinned by tunnel networks. The main one is the Tube, though there are also others for water, sewerage and other services. The Tube network is multi-dimensional, with layers of tunnels, some of which are very deep. Famously, London’s Tube stations were used as bomb shelters in the Blitz: the picture at the head of this post is of Londoners sheltering in Aldwych Station in 1940. They would no doubt be used for this purpose again were there to be a similar blitzkrieg today.

Gaza is also underpinned by tunnel networks. But although they are colloquially known as the “Gaza Metro”, no trains run through them, and there are no stations that could be used as bomb shelters. They have a different purpose. Or rather, several purposes: defensive, offensive - and economic.

Gaza and its tunnels

Gazans first started building tunnels under the Egypt border after the 1980 Egypt-Israel peace treaty divided the border town of Rafah in half. Sundered Bedouin families burrowed under the border to connect with their relatives on the other side. The tunnels ran from one residential building to another, with the entrances either inside the properties or hidden in chicken coops or olive groves. Tunnel operators smuggled in a variety of consumer goods, such as processed cheese (which was subsidised in Egypt but taxed in Israel), and medicines. They are also suspected of bringing in weapons, gold and money for Palestinian militants, particularly during the First Intifada of 1987-93.

After the signing of the Oslo Accords in the mid-1990s, Israel applied a tourniquet to the Gaza economy. In preparation for Gaza’s reunification with the West Bank and the creation of an independent Palestinian state, Israel built a wall around the enclave and progressively tightened controls on the movement of goods and people. Unsurprisingly, Gazans responded by building more tunnels. As a result, Gaza’s economy grew despite Israel’s restrictions. In 1999, when a new corridor between Gaza and the West Bank opened, the tunnel economy expanded to benefit the West Bank too.

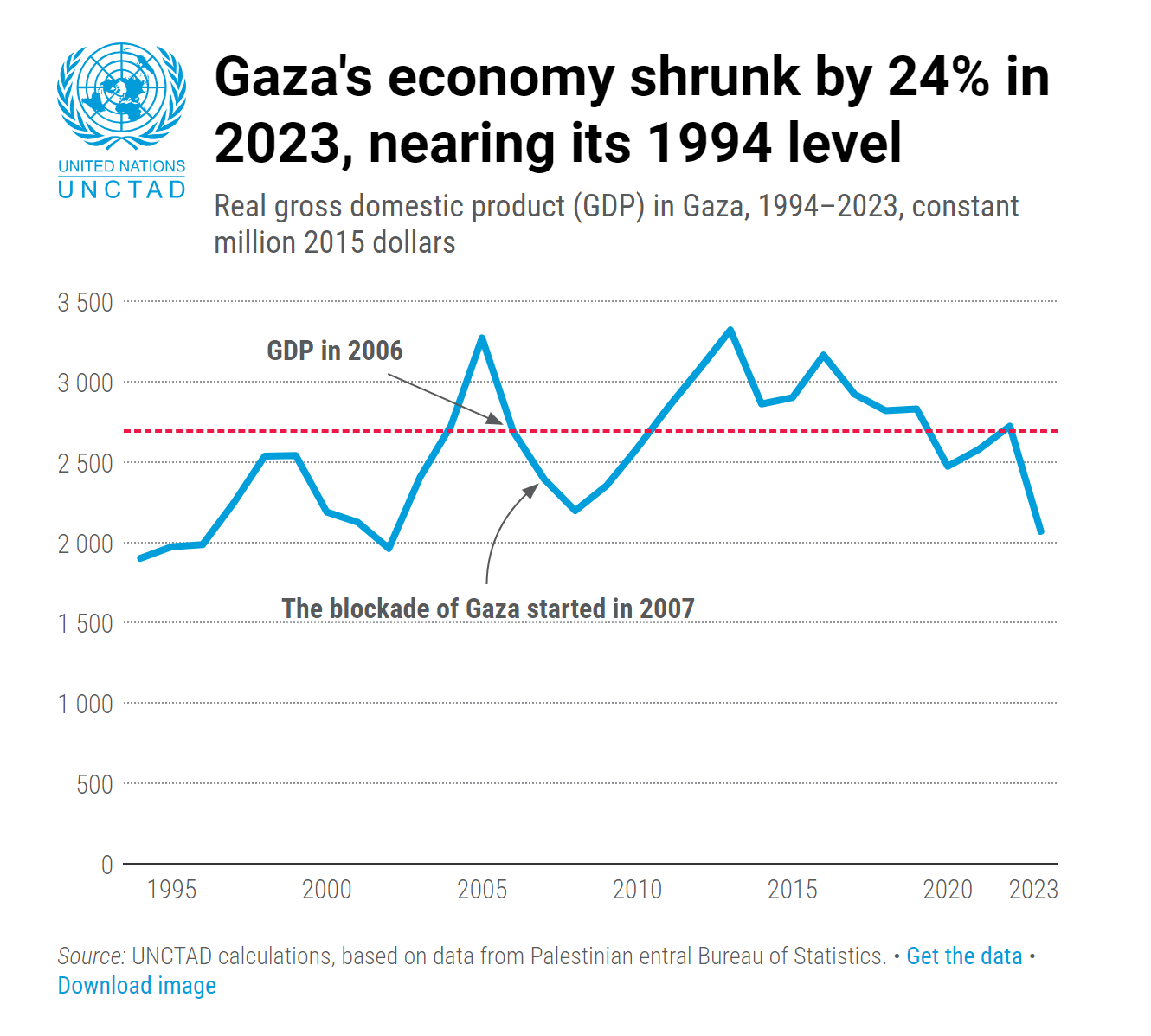

(chart from UNCTAD)

But in 2000, the Second Intifada started. Israel closed the borders, built a bigger and better wall around the enclave, and bombed Gaza’s airport and seaport. In Rafah, it conducted a devastating ground operation, demolishing some 1,500 houses to build a 100m wide buffer zone along the entire length of the Gaza-Egypt border - the so-called Philadelphi Corridor. During this operation, Israel claimed to have discovered and closed down at least 90 smuggling tunnels, though independent agencies say this might be an exaggeration.

Whatever the truth about the tunnels, there’s no doubt that Israel’s ground action in Rafah, and the creation of the new, heavily policed buffer zone, seriously hampered the tunnel economy. Unable to compensate for the loss of land, air and sea connections to the outside world, Gaza’s economy tanked.

But it didn’t stay down for long. The Gazans simply built longer and deeper tunnels, bypassing Israel’s border restrictions and compensating for the loss of air and sea connections. By the time Israel withdrew from Gaza in 2005, Gaza’s economy was booming again. The World Bank, completely ignoring the resurgence of the tunnel economy, incredibly says this extraordinary recovery was due to (unsustainable) fiscal stimulus from the Palestinian Authority, increased bank credit, and some loosening of Israeli restrictions on the movement of goods and people.

In January 2006, elections to the Palestinian Legislative Council, the Palestinian National Authority’s parliament, were held in the Palestinian territories (Gaza, West Bank and East Jerusalem). Hamas (campaigning as Change and Reform) won 75 of the 132 seats on 44.45% of the vote, comprehensively defeating Fatah, its nearest rival. Gaza voted overwhelmingly for Hamas.

Despite most international observers reporting that the elections were free and fair, Israel refused to accept the result. It withheld the tax revenues it collected on behalf of the Palestinian authorities, tightened restrictions on movement of people and goods, and detained several members of the new government. In June 2006, in response to Hamas’s capture of an IDF soldier, Israel sealed the Gaza border. Then, in July, it invaded, briefly occupying part of northern Gaza and launching devastating raids on the Jabalia and Beit Lahia refugee camps.

According to the IMF, the worsening security situation had a devastating effect on the economy of Palestine:

Production has been lost due to outright destruction of physical infrastructure and assets, or dampened by the numerous closures and checkpoints, the shortage of funds to finance government spending, as well as by the increased uncertainty about the Palestinian territories’ prospects.

As the chart above shows, the effect on Gaza’s fragile economy was immediate and dramatic. By the end of 2006 it was shrinking fast. But what happened next surprised everyone.

Blockade and war

In 2007, Hamas seized control of Gaza and evicted the leaders of Fatah. In response, Israel blockaded imports of food and fuel into Gaza, while Hamas fired increasing volumes of rockets into Israel. After Hamas’s brief, and doomed, attempt to force open Egypt’s border, Egypt sealed the border and built a bigger and better wall along the Philadelphi Corridor. Employment in Gaza crashed, and GDP plummeted. Gaza’s economy teetered on the verge of collapse. A humanitarian crisis loomed.

But it didn’t happen. The brutal siege, whose stated aim, according to Israeli sources, was to “keep Gaza’s economy on the brink of collapse,” failed in its objective. Instead, Gaza’s economy recovered - rapidly. From 2008 to 2012, it boomed. The reason was, once again, tunnels.

According to Nicholas Pelham of Columbia University, the Hamas-led government of Gaza presided over a tunnel-building frenzy funded by massive public and private sector investment. Tunnel construction became a principal driver of the Gaza economy and a major source of employment, paying better wages than in many other industries. Israel was blockading building supplies, but no matter, Gazans brought concrete and other materials in through existing tunnels and used them to build more and better tunnels. By December 2008, over 500 new tunnels had been built. Items on Israel’s extensive and arbitrary list of “banned goods” were of course routinely smuggled through the tunnels, but so too were items not subject to the blockade, because it was easier, quicker and cheaper to bring them in through the tunnels. Gaza had become, in effect, a freeport.

Tunnel construction and traffic was forced to pause during Operation Cast Lead, a three-week war from December 2008 to January 2009 in which Israel killed over 1,300 Palestinians, wounded another 5,000 or so and destroyed or damaged large amounts of civilian infrastructure and buildings. The tunnel network was degraded by air strikes on Rafah. But after the war ended, Hamas repaired the tunnels and encouraged the building of new ones.

Under the terms of the international ceasefire that ended the war, Egypt had agreed to take steps to choke off the tunnel trade, including building a 25m deep metal wall to discourage tunnel building. But it was, to say the least, half-hearted about it. Progress on the wall was so slow that in 2011 a frustrated USA withdrew technical assistance. And local authorities continued to turn a blind eye to tunnel building and traffic, on payment of an appropriate bribe. Meanwhile, tunnel operators built longer, deeper and better reinforced tunnels to escape detection, avoid the wall and reduce accidents.

Thus, after the war was over, the tunnel economy continued to boom. Within two years it had expanded tenfold. Prices within Gaza fell to levels that the average Gazan could afford. By mid-2010, according to Pelham, shortages from Israeli restrictions had been reduced “to a considerable extent or more”. The tunnel economy had neutered the import blockade and generated a remarkable economic recovery.

Endgame

It was always unlikely that Israel would for long tolerate such blatant violation of its blockade. The question was merely what it would do about it, and when. But the death of the tunnel economy came sooner than might have been expected, and not solely at the hands of Israel.

In May 2010, Israel’s attack on a humanitarian aid convoy headed for Gaza sparked an international outcry. Although Israel managed to convince a UN investigation that it was totally justified in blockading humanitarian aid, in June 2010 international pressure forced it to lift its ban on the import of commercial goods. This had a catastrophic effect on the tunnel economy. As goods flooded into Gaza, prices crashed. By the end of 2010, half the smuggling tunnels were no longer operative, and many others had reduced traffic. But the export ban was never lifted. By mid-2012, unemployment was rising, and growth had tailed off.

The election of Muslim Brotherhood to power in mid-2012 raised hopes that Gaza could normalise relations with Egypt, enabling above-ground (and above board) trade to develop, further reducing reliance on the tunnels and fostering growth of legitimate export industries and manufacturing.

But it was not to be.

In 2013, a military coup dethroned Mohamed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood President, replacing him with General (subsequently Field Marshal) Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Believing that Hamas was supplying weapons to its ally the Muslim Brotherhood via the smuggling tunnels, Sisi embarked on an aggressive campaign of tunnel closure. By mid-2014, his army claimed to have closed 1,659 tunnels. In December 2014, Sisi expanded the Philadelphi Corridor buffer zone to 5 km, longer than most tunnels. And in September 2015, apparently in collaboration with Hamas’s defeated rival Fatah, Egypt started pumping sea water into the tunnels, rendering them completely unusable and causing major environmental degradation.

Simultaneously with Egypt’s closure of the tunnels, Israel embarked on another war. Operation Protective Edge, launched in July 2014 in response to an outbreak of violence in the West Bank and a larger than usual rocket assault from Gaza, lasted for seven weeks, during which large parts of Gaza’s civilian infrastructure and buildings were yet again ravaged.

The combination of Israel’s war with Egypt’s closure of the tunnels tipped Gaza into recession, and although the subsequent aid-financed rebuilding briefly generated some economic growth, it proved unsustainable. Gaza has never recovered from the destruction of its tunnel economy.

The ghosts of the past

Eylon Levy implies that the entire tunnel network was built by Hamas solely for military purposes, and diverted resources that could have been used to develop Gaza’s economy. But this isn’t true. Most of the tunnels were built by private sector operators for economic purposes, and although Hamas’s tax revenues from tunnel traffic were no doubt partly used to pay for weapons and military infrastructure, the smuggling itself caused Gaza’s economy to boom and enabled the rebuilding of its shattered physical infrastructure. Indeed, so successful was the tunnel economy that for a while it looked as if Gaza could even end its dependence on Israel and international aid - a commitment Hamas had made in its election campaign of 2006.

In fact the tunnel economy always contained within itself the seeds of its own destruction. It was great for imports, but not so much for exports. Egypt wouldn’t officially allow exports to circulate in its economy, and exports to other places were rendered impossible by Israel’s continuing blockade. An economy that can import but can’t export is unsustainable. Gaza’s tunnel economy generated a lovely construction boom and import-led consumption boom, but as Greece could tell you, this is ultimately unsustainable. Gaza needed the export blockade to be lifted. It still has not been. That, fundamentally, is why it couldn’t recover from the 2014 recession - and couldn’t rebuild its tunnels.

Whatever tunnels now exist in Gaza, they aren’t significantly used to smuggle goods. But they aren’t, as Eylon Levy claims, purely military, though those that are still usable have perhaps been turned to military purposes. Rather, they are the ghosts of the past, an empty reminder of the tunnel economy that was washed away in the floods.

Related reading:

Gaza’s Tunnel Phenomenon: The Unintended Dynamics of Israel’s Siege - Nicholas Pelham, Columbia University (pdf)

Preliminary assessment of the economic impact of the destruction in Gaza - UNCTAD

Image of Aldwych Station in 1940 from the London Transport Museum.

Refreshing to get a cool analysis of Gaza from an economic perspective, and how they have managed to survive and even thrive in the face of all that all-powerful Israel has thrown at them over decades. When every move made - man, woman or child - is monitored by Israeli drones who may choose to attack, it is hardly surprising that tunnels have become a vital set of arteries over the years.