The people most affected by the Government's welfare reforms are not the people you think they are

Political discourse is all about young people - but it's older people who will bear the biggest impact.

Who exactly are the people most affected by the Government’s welfare reforms?

To hear politicians talk, you’d think it is young people. On Politics Live last week, an extraordinarily ill-informed panel waxed lyrical about young people not in employment, education or training (NEETS), workless households and the need to get unemployed people into work. Not a single person mentioned that neither PIP nor Universal Credit is an out-of-work benefit, and that about a fifth of PIP claimants are working. Politicians across all parties (with the honourable exception of the Greens), and the whole pundit class (with the honourable exception of independent journalists such as Chaminda Jayanetti, who wrote this astonishing piece of investigative journalism), are laser-focused on getting more people working to restore the economy. Like that’s never been tried before.

But this doesn’t add up. We know that people’s health declines as they get older, so PIP and incapacity benefit claims would surely rise with age. And we also know that state pension age has been rising, so more older people are expected to work: this too would tend to increase incapacity benefit claims. Furthermore, we know that the proportion of older people in the population is rising due to the 1960s baby boom and recent low birth rates: again, this would tend to increase the volume of incapacity benefit claims. If I wanted to impede the rise in disability-related welfare bills (to be clear, I don’t), I’d be looking at restricting the benefits of the old, not the young.

I think that’s exactly what the government is doing. But they are not being honest about it, because let’s face it, targeting older people is never a vote winner.

Here’s the evidence.

People over 50 are the biggest group of PIP claimants

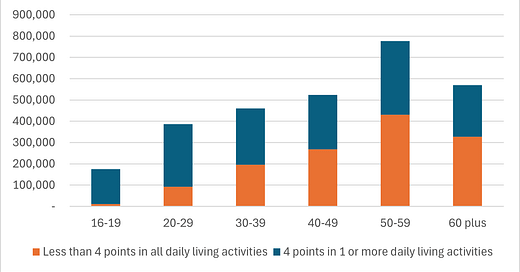

In a comment on my last post, Paul Bivand linked a Freedom of Information response from the DWP which provided figures for PIP/DLA claimants by age group, split by those scoring 4 points in 1 or more daily living activity and those scoring less than 4 points in all daily living activities. I have put those figures into this chart:

(please note that this is a bit of a chart crime, the first and last bars on this chart are not full deciles)

Why the 4 points/less than 4 points split? Because the Government proposes to remove PIP from those who score less than 4 points on all ten daily living activities. Those are the people in the red bars on the chart.

The chart shows that PIP is most likely to be claimed by people over 50. And of those, over half will not qualify for PIP (and, by extension, for the health-related uplift to universal credit) under the proposed welfare reforms. For people aged 60-66, it is 58% of PIP claimants.

The Government’s concession enabling existing claimants to keep their benefits merely delays the impact. From November 2026, people in the red bars who would under current rules have qualified for PIP will no longer do so, and some will also no longer qualify for health-related universal credit or ESA. More than half of these people will be over 50. For some of them, it will mean abject poverty.

The DWP's figures also show women are more likely to score less than 4 points in all activities than men (52% against 39%). So women are more likely than men not to qualify for PIP or other benefits.

The “chronic pain” problem

Why are women more affected by the proposed reforms than men? This chart that I have created from the DWP’s figures (in the same FOI response) offers a clue.

The chart shows that arthritis, back pain, chronic pain sydromes such as fibromyalgia, and other musculoskeletal pain attract fewer PIP points across all daily living activities than all other conditions. Among those claiming PIP because of arthritis, 79% do not score 4 points in any daily living activity: for back pain, the figure is 77%.

Under the Government’s proposed reforms, from November 2026 most new claimants who under current rules would qualify for PIP because of chronic pain conditions including arthritis will no longer qualify. Since a successful PIP claim will become the gateway to the health-related element of Universal Credit, they won’t qualify for that either. The drop in income for these people compared to current claimants with equivalent conditions could run to thousands of pounds per annum.

Chronic pain conditions disproportionately affect women, particularly older women. Fibromyalgia is almost exclusively a female condition, with women making up 80-90% of diagnosed sufferers, and women are also more likely to suffer back and neck pain and to develop arthritis as they grow older. A 2017 study by Versus Arthritis found that women are more likely than men of the same age to suffer chronic pain, and the pain is more likely to be severe enough to make everyday living activities difficult (“high impact chronic pain”). 14% of women suffer from high impact chronic pain, but only 9% of men.

Versus Arthritis also found that chronic pain was more prevalent among Black people than other ethnicities.

We don’t know why the PIP assessment appears to discriminate against people with chronic pain conditions. But this observation from Versus Arthritis’s report might have something to do with it:

Chronic pain has been called an invisible condition. Although often devastating to the millions who have it, to others it cannot be seen. Pain isn’t easy to report or record and can’t be measured objectively. It does not show up on a blood test or on scans. We rely on the words of people with chronic pain to describe it – and yet so often it is simply indescribable. For those not living with chronic pain, its debilitating effects can be impossible to imagine and empathise with.

Whatever the reason, the fact remains that chronic pain conditions disproportionately affect older women, and their disabling effect is not properly recognised in the current PIP assessment. The Government’s reforms will therefore also disproportionately affect older women.

A recent report argued that the Government’s reforms discriminate against women because the PIP assessment process fails to take account of women’s particular needs, for example in managing menstruation. I think there is also a case that the reforms discriminate on grounds of age and sex combined, because of their disproportionate impact on older women.

Rising claims for mental health problems

Discussions I have seen in the press about the Government’s reforms focus on high and rising claims for anxiety and depression. This is understandable: the chart above shows that anxiety and depression is by far the largest health category for PIP claims. But what is not understandable is the abysmal quality of the discussion around this. To hear Government ministers and self-appointed pundits talk, you’d think anxiety and depression were conditions primarily experienced by young people and the solution is to give them training and help them into work so they don’t fall on the scrap heap of life.

But this is not what the figures show. According to the website Benefits and Work, the people most likely to claim PIP for anxiety and depression are middle-aged and older:

(note the bands are extremely unequal: per year of age, fewer young people claim PIP for anxiety and depression than this table suggests, and more people over 50 do).

Training and opportunities targeted at young people are important, but they are not going to help the majority of those claiming PIP for anxiety and depression. It would be useful to understand why the claims drop off sharply after 65: could the fact that people past state pension age have a guaranteed income, are mostly mortgage-free, and aren’t expected to work have anything to do with it?

The IFS notes that mental health conditions are becoming more common in the working-age population: in surveys, 13-15% of working-age adults report mental health problems, up from 8-10% in the mid-2010s. Most surveys show the upwards trend starting well before the Covid pandemic. The IFS says this cannot explain the sudden rise in disability benefits claims after the pandemic.

However, working-age mortality rates have risen since the pandemic, and this does seem to be connected to rising severe mental health problems:

In 2024, the working-age mortality rate was 1.5% above the 2015–19 average – equal to 1,200 additional deaths after adjusting for changing population size and age. In 2023 (the latest year with data on cause of death), the mortality rate was 5.5% above the 2015–19 average – equivalent to 4,400 additional deaths. Most of the additional deaths were ‘deaths of despair’ – deaths due to alcohol, suicide or drugs. After adjusting for changing population size and ageing, there were 3,700 (24%) more working-age ‘deaths of despair’ in 2023 than the 2015–19 average. People with mental health conditions are at much higher risk of ‘deaths of despair’, so the rise in these deaths is consistent with an increase in (severe) mental health problems.

We have a mental health crisis among working-age adults. There’s no evidence that young people are causing it. Rather, the primary source appears to be a lot of very unhappy middle-aged people. How is cutting the benefits awarded to working-age adults claiming benefits for mental health problems supposed to fix this? Shouldn’t we be trying to find the cause of their misery, and fix that?

It’s all about keeping older people in work

Despite all the Government's rhetoric about young people and the need for training and opportunities, the reforms will mainly affect people over 50, especially women. So it's not about getting young people into work. It's about stopping older people from leaving.

Helping older people with health problems, disabilities and caring responsibilities to remain in the workforce is a good thing. Paid work doesn’t merely improve people’s living standards, it’s important for dignity and social connection too. Ideally we want people to continue working for as long as possible, even after state pension age. But the sad fact is that many employers do not want to adjust their working practices to accommodate the needs of people with health problems, disabilities and caring responsibilities. They prefer to force them out.

Take my my friend Alice*, who was a senior nurse practitioner in the NHS. At the age of 60, suffering from back pain and arthritis, she asked management if she could reduce her hours. They refused, and instead offered her a part-time teaching post at a considerably lower salary. She didn’t want to teach and objected to the pay reduction, so she took early retirement. “I love my job,” she told me. “I didn’t want to leave. But I couldn’t continue.” What a terrible loss to the NHS. And how utterly stupid of the management to refuse to accommodate her request for reduced hours.

If the government really wants to keep older people in the workforce, it needs to address poor management practices such as this that unnecessarily force them to take early retirement, and in many cases, to claim PIP and incapacity benefits until they reach state pension age. These charts from the OBR show how incapacity benefit claims increase with age:

Increasing the state pension age increases the volume of incapacity claims, because many people with health problems, disabilities and caring responsibilities who would previously have received the state pension are forced on to working-age benefits instead. This pair of charts shows how the volume of incapacity benefit claims from women in their 60s increased in the 2010s as women’s state pension age gradually rose to 66:

Alice was one of the women affected by state pension age rises. She doesn’t claim incapacity benefits, but many women of her age who were forced to leave work because of chronic pain and disability do.

The Government’s reforms won’t affect Alice and her peers. But unless government forces employers to offer the Alices of the future a better deal, they will still be forced into early retirement. Making them ineligible for incapacity benefits won’t keep them in their jobs, and it won’t conjure up other jobs they are capable of doing. It will just make them poor.

Why are we even doing this?

The Government’s reforms will particularly hit people in their 60s. This is because the older someone is, the more likely they are to be in poor health. The ONS estimates “healthy life expectancy” in England as 61.5 for men and 61.9 for women: after that age, the likelihood of developing significant health problems and disabilities rises dramatically. Many older people develop multiple health problems that together add up to serious disability despite none of them qualifying for the magic 4 points. The Government’s proposed reforms take no account of these co-morbidities.

From November 2026, people - predominantly women - who have multiple health problems and don’t have adequate private or occupational pensions will be deemed unemployed, not disabled, and be given poverty-level benefits to encourage them to look for work. But in the absence of measures to force employers to change their ways, what realistic prospect of employment will they have? And why do we want to force them to look for work anyway? What benefit would this bring to the economy? Perhaps some might find work. But at what cost to their health - and to the NHS?

This isn’t welfare reform, it’s cruelty.

*Not her real name

Related reading:

The “deserving poor” are the latest target of Government cuts

Why the Tories’ “put people to work” growth strategy has failed

Now state pension ages are equalised, let’s fix the real problems